What could the Chicago runoff look like?

Looking ahead at Chicago's mayoral runoff and projecting electoral coalitions

It’s been over a month since the first round of Chicago’s municipal elections, and the runoff is days away. A tight contest has developed in the mayoral race between conservative-leaning former education superintendent Paul Vallas and progressive-leaning county commissioner Brandon Johnson, both of whom emerged from the crowded primary ahead of incumbent Lori Lightfoot. In this article, I discuss the lead-up to this election and explore what the runoff map could look like.

Background

The first round was a crowded, hotly contested race between five major candidates. The incumbent mayor, Lori Lightfoot, won in a landslide in 2019 but quickly made enemies left and right — double meaning intended. As with most big city mayors, crime has been a political flashpoint under her administration, and her attempts to straddle a line pleased no one and alienated both the police union and progressive police reform advocates. She also made enemies on the city council in part by limiting the council’s power and feuded with Governor J.B. Pritzker over power and over the governor’s progressive political reforms.

Seen as highly vulnerable in the lead-up to her re-election campaign, Lightfoot drew four high-profile challengers. Two came from the right: businessman Willie Wilson, an eccentric perennial candidate who has consistently drawn support from roughly a quarter of Black Chicagoans in his two previous mayoral campaigns and his independent Senate campaign; and Paul Vallas, former school superintendent in Chicago, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Bridgeport, Connecticut, who developed a record of school privatization and antagonism toward teachers’ unions. Both focused their campaigns on crime, aligning with “law-and-order” and tough-on-crime positions.

Two came from the left: Congressman Chuy García, a longtime stalwart of the Chicago progressive movement and heavyweight of the Mexican community on the city’s Southwest Side, who unsuccessfully challenged Rahm Emanuel in the 2015 mayoral race before taking up his current position; and Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson, a former educator and labor organizer whose candidacy was pushed by the Chicago Teachers’ Union. Four other candidates also ran — activist Ja’Mal Green, State representative Kam Buckner, and alderpeople Sophia King and Roderick Sawyer — but none registered significant vote shares.

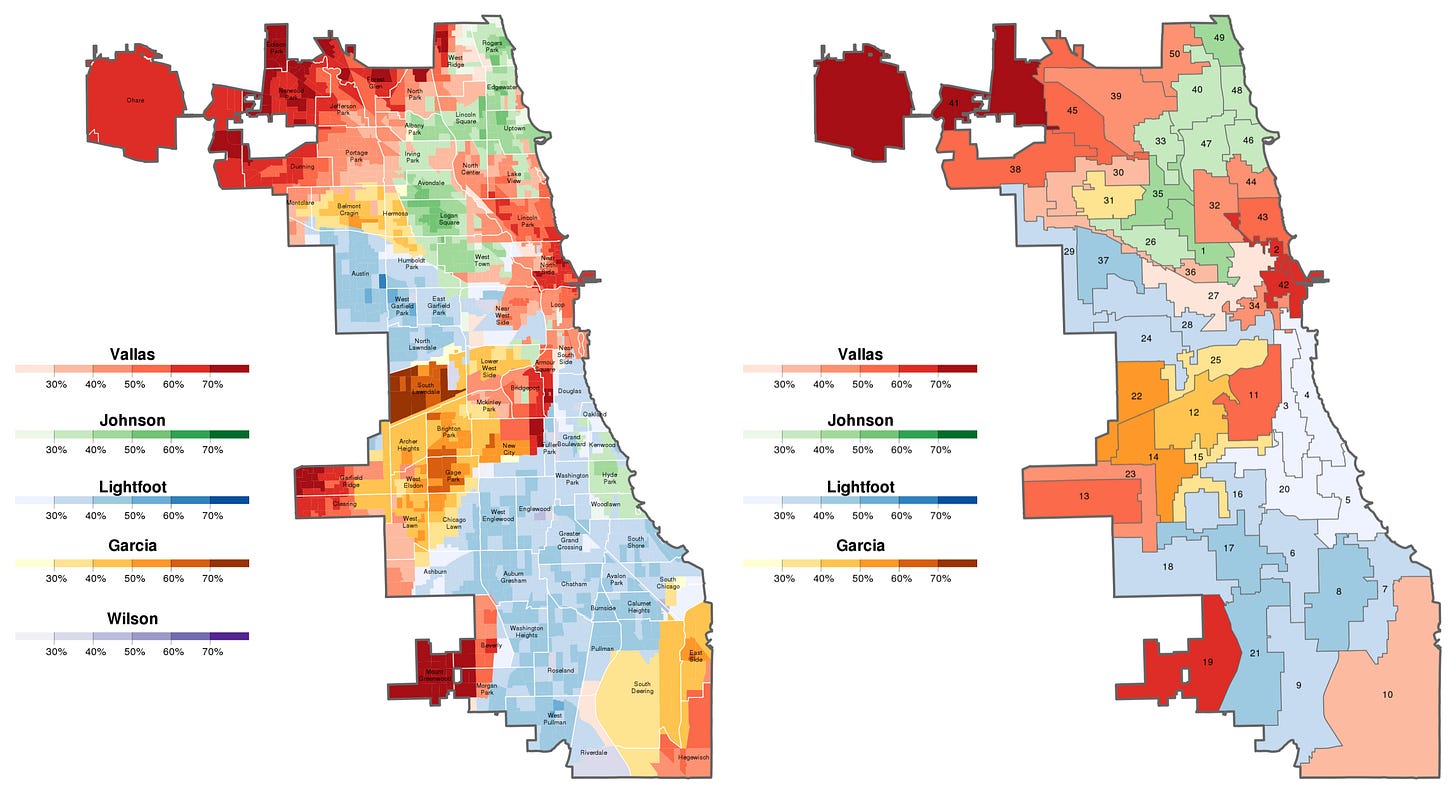

Thanks to the highly racialized nature of voting in Chicago, candidates’ bases conformed significantly to race and geography, not only to ideology. Black voters were split three ways, with the plurality (mostly establishment-leaning liberals) opting for Lightfoot, while conservatives supported Wilson and progressives supported Johnson, and other candidates registered little support. García won overwhelmingly with Southwest Side Latinos, though a significant minority (mostly conservative-leaning voters) went for Vallas, and on the Northwest Side, where the Latino community is mostly Puerto Rican rather than Mexican, García commanded weaker loyalty and a number of voters selected Johnson. Vallas benefited from being the only white candidate in the race, unlike 2019 when he was one of six, and won overwhelming white support in the wealthy near North Side lakefront areas, the conservative far Northwest Side, and police-heavy pockets on the far Southwest and South Sides. White liberals and progressives on the Northwest Side and the far North lakefront, who formed Lightfoot’s strongest base in 2019, largely abandoned her for Johnson this time around, a crucial demographic that Lightfoot and García were also competing for; these voters helped carry Johnson over the line ahead of them.

Ultimately, Vallas finished first with 33% of the vote, followed by Johnson with 22%, Lightfoot with 17%, García with 14%, and Wilson with 9%. Vallas’s first round win was widely anticipated, though the margin of his lead was a surprise, and Johnson’s advancement to the runoff was considered an upset, as he was deemed a contender but a weaker one than Lightfoot and García.

Below are precinct-level and ward-level maps of the first round, courtesy of Wikipedia user Twotwofourtysix, demonstrating each candidate’s strengths. An interactive map can also be found here.

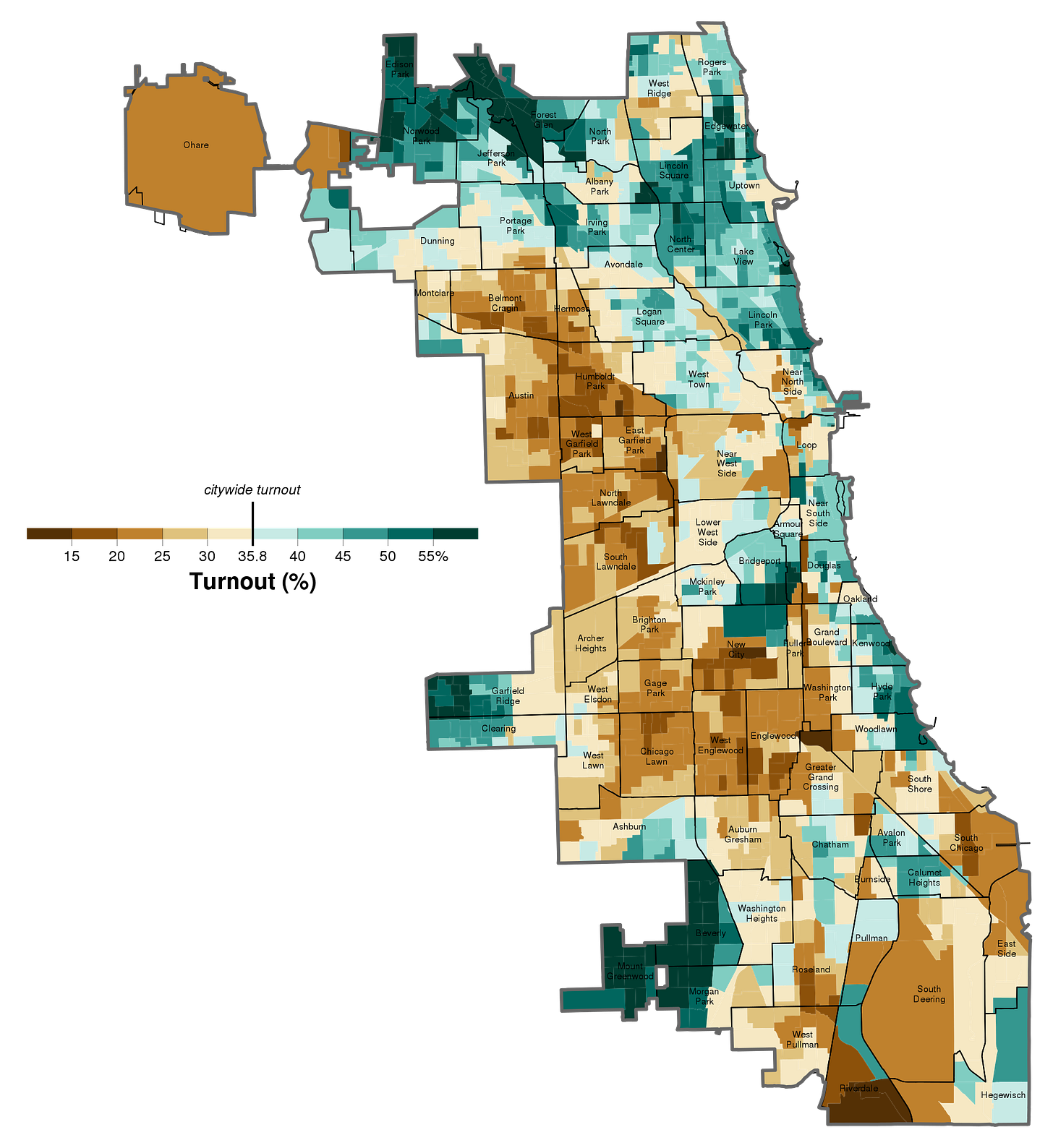

As the second-place finisher in the first round, Johnson obviously has a steeper hill to climb to reach 50%. That being said, he also has more room to grow in support since his first round support occupied much less of the Black lane than Vallas’s did of the white lane. He could also stand to benefit from boosting turnout, as the city’s whiter neighborhoods far outpaced its mostly Black (and Latino) neighborhoods in first round turnout:

The runoff campaign has unfolded as expected, with each campaign aiming to paint the other as too extreme. Vallas has tried to negatively portray Johnson as beholden to the Chicago Teachers’ Union and to tie him to the “defund the police” movement; though Johnson does not support reducing police funding (to the dismay of many progressives), he had endorsed the goal in the past. Johnson has highlighted Vallas’s connections to Republicans, including past statements where he called himself “more of a Republican than a Democrat” and his affiliations with anti-LGBTQ and anti-abortion groups, and criticized his record in the education sphere, rolling out an ad featuring endorsements from Congressmen Troy Carter of New Orleans and Brendan Boyle of Philadelphia, both of whom decried Vallas’s legacies as destructive to public education in their cities.

Wilson endorsed Vallas in the runoff, which was expected due to their similar politics, while Lightfoot made no endorsement (which is probably for the best, as any endorsement of hers would probably hurt the endorsed candidate). It’s likely that a number of Wilson voters will follow his lead and vote for Vallas over conservative politics and crime fears, but most Black voters will probably line up behind Johnson thanks to racial voting. García has endorsed Johnson, but it’s unclear if Johnson can win most of his voters, and most polls show Vallas winning among Latino voters. Though Vallas is not Latino, he is helped by his (Greek) last name, which is Spanish-passing enough that a recent poll found one-third of Latino Chicagoans think Vallas is Latino.

In addition to failed first round contenders, the two candidates have sought and collected endorsements from a wide variety of other policians. Both have added dozens of state legislators, alderpeople, unions, and political organizations to the ranks of their backers. Johnson has also picked up the endorsements of a number of notable Congressional Black Caucus members, including Jim Clyburn; Reverend and former presidential candidate Jesse Jackson; Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren; and Illinois’s own Carol Moseley Brown, the first Black woman in the Senate. Current Illinois Senator Dick Durbin has endorsed Vallas, as have Congressman Bobby Rush and former Education Secretary Arne Duncan, who previously succeeded Vallas as Chicago’s public education head.

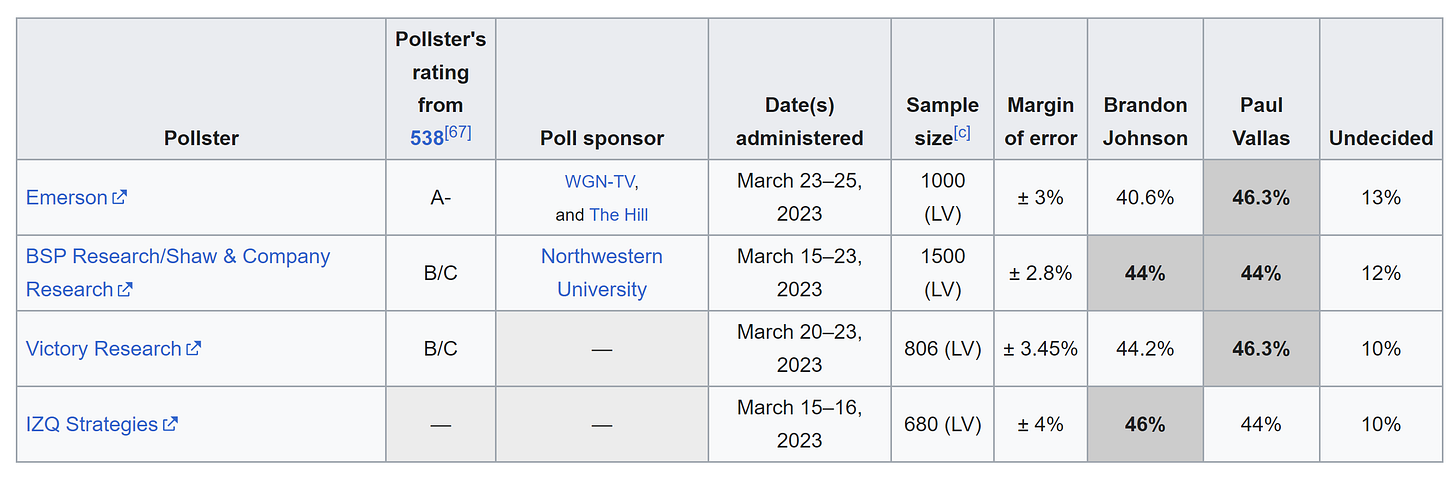

Overall, polling is split. Of the four polls conducted in the past two weeks, two show a Vallas lead and one show a Johnson lead (all narrow), while one suggests a tie. It’s clear that this race is anyone’s game.

Runoff projection

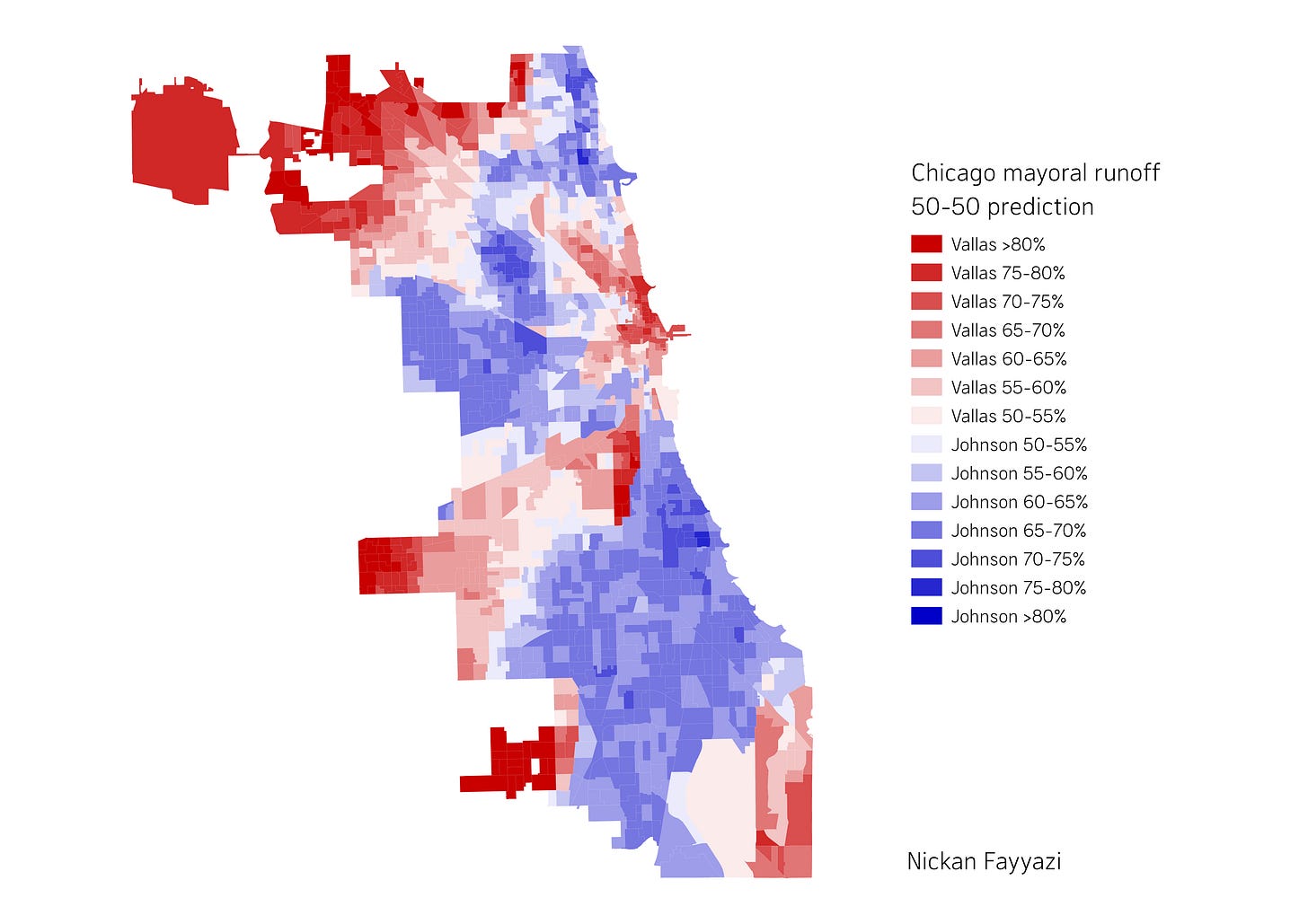

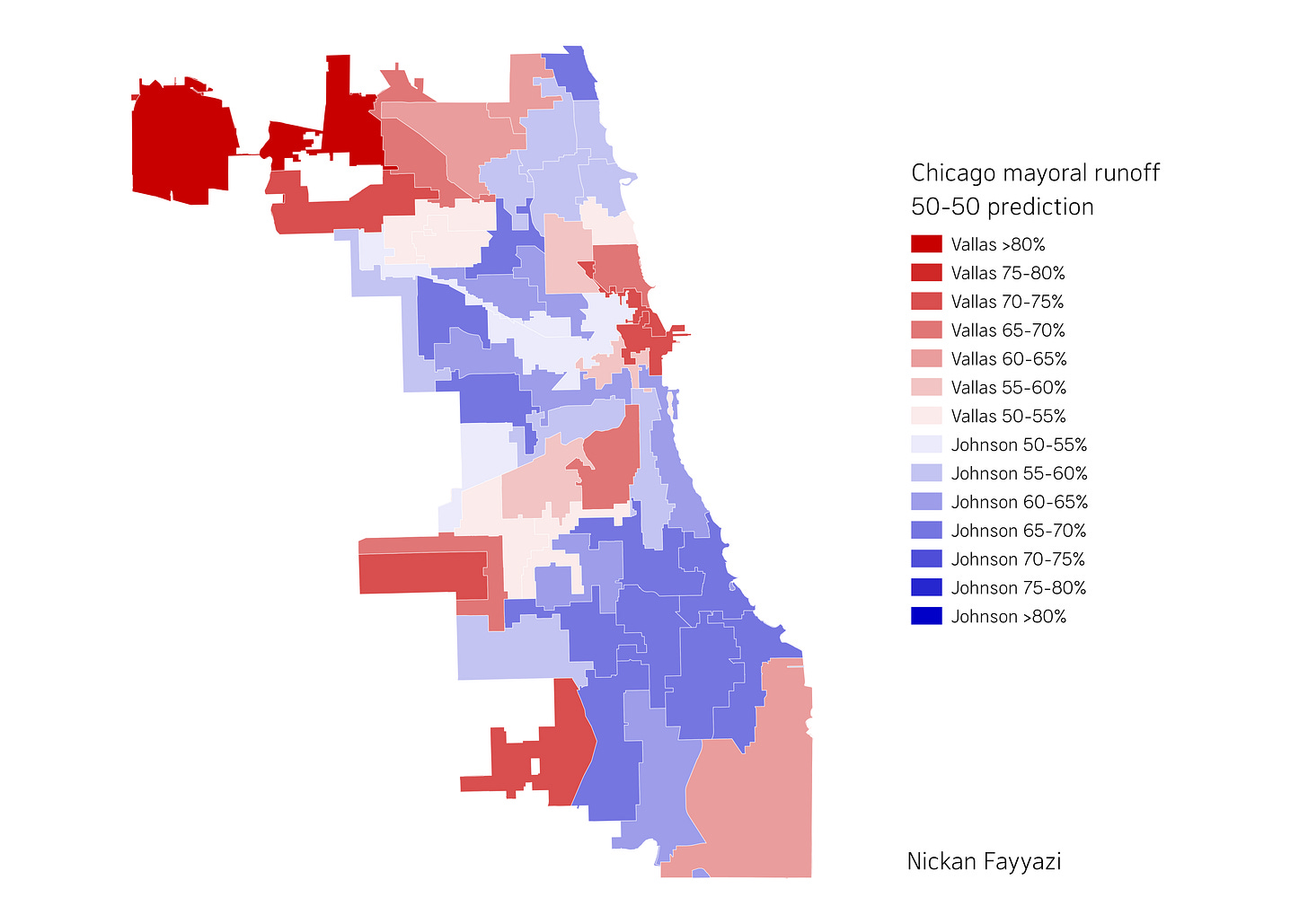

Given the fascinating first round results and the intrigue that this closely-fought runoff has brought, I thought it would be interesting to project what the results of the runoff election could look like. I’ve concerned myself more with predicting electoral coalitions and the geographic distribution of votes rather than predicting a winner, so this projection is based on a tied citywide result.

My rough estimate was to split Wilson and García voters 50-50 and to split Lightfoot and minor candidate voters 75-25, based on rough estimates of how those groups might distribute themselves in the runoff vote, intentionally using simple fractions to avoid getting bogged down in minutiae.

I downloaded first-round precinct-level results, calculated a runoff projection in each precinct using the above formula (keeping turnout equal), and combined the resulting spreadsheet with a precinct shapefile in QGIS to produce a map:

Naturally, each candidate maintains their first-round strengths: Johnson in progressive neighborhoods on the Northwest Side (e.g. Logan Square, West Town, Albany Park), far North Side lakefront (Uptown, Edgewater, Rogers Park), and Hyde Park; Vallas in wealthy lakefront neighborhoods (Lincoln Park, Near North Side, the Loop), blue-collar white Armour Square, and conservative pockets on the outer reaches of the city (the far Northwest Side, Clearing, Garfield Ridge, Mount Greenwood, Hegewisch) with significant police populations.

Johnson dominates all majority-Black neighborhoods on the South Side and West Side, expanding his existing first-round lead over Vallas in those areas. Executing this in reality will be crucial to his chances of victory. As these areas had fairly similar first-round results across the board, their runoff results are similarly consistent here; Johnson wins 60-70% of the vote in nearly all majority-Black precincts here.

Majority-Latino neighborhoods on the Southwest Side, as well as the East Side and the Belmont Cragin and Hermosa neighborhoods on the Northwest Side, all of which García won in the first round, split fairly evenly but narrowly in Vallas’s favor here, with the exception of progressive Pilsen, which is represented by socialist Byron Sigcho-Lopez on the city council. This is thanks to Vallas’s first-round performance, in which he outpaced Johnson in most Southwest Side areas to finish a comfortable second behind García. As a result, even if Johnson does capture a majority of García’s voters in the runoff, it will be an uphill battle to win these neighborhoods.

The map bears a resemblance to multiple past elections, in particular former mayor Harold Washington’s 1983 and 1987 general election wins against Bernard Epton and Ed Vrydolak, respectively, and current Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s 2022 primary and general re-elections, all of which saw Black progressives emerge victorious over challengers from the right.

I aggregated the same data at the ward level and produced a corresponding map:

Johnson wins 29 wards to Vallas’s 21 here. This despite a tied citywide result is because Vallas has more landslide wins (surpassing 70% in six wards compared to none for Johnson) and because his wards tend to have higher turnout (an average of 10,809 votes in Johnson wards compared to 11,954 votes in Vallas wards). This demonstrates a weakness in Johnson’s electoral coalition, which would greatly improve its chances of forming a majority if turnout were level across all demographics.

All 16 majority-Black wards go to Johnson; he surpasses 60% in 13 of them (with the rest having relatively smaller Black populations) and 65% in 9. Of the 14 majority-Latino wards, he wins 6 to Vallas’s 8 (winning 4 of the 6 on the Northwest Side, 2 of the 7 on the Southwest Side, and losing the far South Side ward), and 9 of these 14 wards feature no candidate reaching 60% of the vote. Vallas wins the majority-Asian ward, putting up strong margins in both Chinatown and the whiter Armour Square and Bridgeport neighborhoods of the ward. Of the 19 remaining wards, most of which are majority-white (but some of which are more ethnically diverse), Johnson wins 7 and Vallas wins 12.

Johnson’s three strongest wards — 5, 24, and 8 (67% in all three) — are majority-Black, though his fourth-strongest ward, 49, located in Rogers Park on the far North Side, is a fairly diverse and progressive area. Vallas’s three strongest wards — 41 (80%), 13 (73%), and 19 (72%), all consist of police-heavy neighborhoods, and his fourth-strongest, 42, is a wealthy central ward containing most of the Loop, Streeterville, and River North.

Whatever outcome occurs on Tuesday will of course have a significant impact on Chicago politics. The result will very likely be the closest since Harold Washington’s groundbreaking 1983 victory, to which this election contains many parallels. The political coalitions of each side of this race, some reflecting new trends and others reemerging from coalitions past, will be key as the upcoming four years of a new mayoralty play out. In terms of these coalitions, I look forward to seeing how well my map holds up.